CHAPTER XIII. FLASHBACK, by A. Keith Borrowdale, with an inserted contribution by Margaret K. Sherwood

WE PLUNGED FORWARD. The Yellow Cloud was all about us, veritably a typhoon. We could see little at first, but Dr. Kalkenbrenner had swung the tractor around in the direction at least which we knew Katey and the others to be taking—and suddenly there was unexpected help for us from Malu. He, with his highly developed telepathic powers—guided perhaps by the plants on the plain surrounding, perhaps by unconscious impulses from Michael, his old companion—he indicated the path we should take through the opaque yellow wall before us.

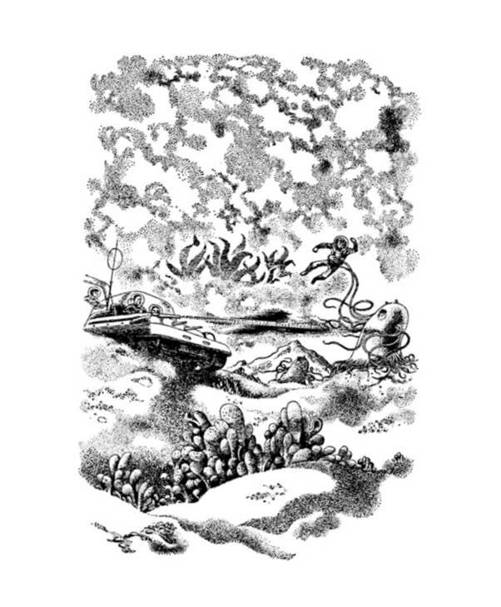

“The flame guns,” cried Kalkenbrenner’s voice within my helmet. “They can do no harm to Maggie and the others—but they can clear a path for us and deal with those other creatures.”

I operated the controls at once, and out from the long nozzles mounted on the tractor’s front part shot two widening fans of flame. The typhoon swirled and dispersed in great swathes before them—my senses were full of a conveyed impression (how can I otherwise describe it?) of primitive agony: a myriad small tortured voices from the spores themselves seemed to scream within my head.

On and on. The distance was short enough—barely a mile—but despite Malu’s general guidance we still had to grope, to hold back on our speed lest we should lose our friends in the yellow tempest. I looked around. In the cloud-free bubble in which we traveled, created by the flame throwers, I could see the lost explorers in the trailer with Jacky and Paul. MacFarlane peered desperately into the mist ahead, as did the two young people. But McGillivray, strangely, seemed to be writing—stooped over a leaf of paper on his knee, his expression remote and concentrated—and with, it seemed to me, an extraordinary (how shall I put it?) sadness in it. I saw him, at one moment, break off his writing to lean close to Malu, as if consulting him; then he set to writing again, guiding the pencil sightlessly across the page, oblivious, it seemed, to the whole wild moment.

It was, perhaps, a full ten minutes before we came upon our friends. We began to fear indeed that we had passed them—that in their flight they had swung around from the track we pursued, that Malu’s instinct had led us astray. But suddenly, in one vast parting fold of the mist before us, we saw them—saw Mike and Maggie firing furiously into the great bodies of the Terrible Ones as the monsters closed around them. One—the largest, immense and hideous, the great blank “face” all spattered with useless bullet holes—encircled Katey in his side tendrils, lifted her high into the air and turned to plunge back toward the Ridge.

The tractor swung dangerously—rocked in its tracks across the loose soil; but Kalkenbrenner had achieved his purpose—the monster was within my range. I wrenched at the controls of the third and deadliest flame thrower—directed its searing blast in a bright ribbon toward the immense squat trunk of Katey’s captor; and saw her fall unharmed to the ground as he writhed, releasing her—as his loose fungoid “flesh” gaped horribly and withered in the heat.

The monster was within my range.

Mike and Maggie, answering our cries through the communication apparatus, had turned toward us and now sped rapidly to where we had halted. Mike lingered, to ascertain that Katey was unharmed—helped her to rise, stumbling a little, then thrust on, his arm in hers. Behind, as I swung the flame thrower to blast and rout the other attackers, Paul and Jacky had opened the tent covering of the trailer. A moment later and all three of our companions were aboard.

And in that moment—that desperate hurried moment—something else had happened, something which, for all its gallant tragedy, was the saving of us indeed. What it was will be recounted in due and proper order; for the present, and to complete all aspects of the story as it progresses, I break the editorial rule and insert here a brief contribution by the one member of the expedition who has not so far set pen to paper. She claims to be no writer—and it has been, I confess, a task of the utmost difficulty to persuade her to take part at all in this compilation. But some account must be given of the adventures of the three members of our party who were, if only for a mercifully brief space of time, face to face with one of the Vivores themselves. The account begins from the moment when Katey turned back from the Albatross to fetch MacFarlane’s fatal chocolate. Our contributor’s language is her own, her method perhaps unique. The very title she has chosen for her short paper is characteristic, both of herself and her boon companion Michael. It is:

OLD JELLYBAGS

An Inserted Contribution to

the Narrative of A. Keith

Borrowdale

by

Margaret K. Sherwood

Kind folks and gentle people:

Shot One: mid-distance: self and K. Hogarth ambulating across from Albiwalbibalbitross for chocowocobocolate. (Used to know a fellow in film business, so this is all film-script stuff: also, of course, anky ooyi eekspi ubbledi-utchdi?) Wham!

Shot Two: close-up self and K. Hogarth in the soup. Yessir. Thick soup. Pea soup. Yellow pea soup. Ellowyi-oudcli.

Dialogue: self and K. Hogarth:

“Guess this ain’t so hot, Maggie.”

“Guess it ain’t, Katey.”

“What do we do now, Maggie?”

“Guess we’d better try to get over to the Albiwalbi with the otherswi, Ateyki.”

“Okey-dokey, Aggiemi. Ouch!”

This final exclamation (literary stuff now—leaf out of Jacky’s book) was occasioned by the sudden looming appearance through the encircling fog of some creatures hitherto beyond our ken, but which we recognized instantly from previous descriptions as some of the celebrated Terrible Ones. (How’m I doing?)

Shot Three or Whatever-It-Is: self and K. Hogarth snatched up in arm tendrils of same and before we knew where we were, there we were, padding off into the orestfi.

Sound Track: plenty of excitement music: idle-iddle-pom, iddle-iddle-pom, pom-pom-pom-pom-iddle-iddle-pom-pom.

Captured!

In this extremity what will befall our two heroines, swept off into the deadly Martian Forest by the hideous monsters known as the Terrible Ones? There they are, pinned to the trunks of two of the Martian Ridge plants, awaiting with fortitude whatever fate may now befall. Will they escape? See next week’s exciting instalment. A Sherwood Production.

Installment Two:

Enter Two-gun Malone, the Boy Wonder of the Martian Wastes. Yippee.

Desperate Dan Malone leaps wildly across the forest floor. Hopalong Malone does his best, firing from all fifteen barrels. Destry Junior to the rescue! Will he make it?

O.K. folks. Answer very simple.

Destry Junior doesn’t make it.

Destry Junior is one blamed three-star Fool.

Gesture much appreciated by self and K. Hogarth. Damsels in distress—welcome sight of gallant rescuer. But gallant rescuer ought to have known better.

Gallant rescuer is also captured.

Cut.

Scene Twenty-five: one hour later: self, K. Hogarth and Dead-eyed Dick Malone still prisoner.

Where are their friends—last seen on their way from spaceship with supine figures of Oldtimer Martian Settlers, Doc McGillivray and Hank MacFarlane? Nobody knows.

On all sides (literary stuff) there is an impenetrable wall of the deadly seed spores. Yet it is a curious aspect of the phenomenon that the intrepid captives are themselves in a space which has been kept clear, a bubble, as it were, in the surrounding ellowyi-oud-cli.

Close-up: Old Jellybags himself.

Kind friends and gentle people: what do I say now? How do I go on from here?

There he was, plumb in the center of a great slob of marsh, and there was steam rising up all around him. He was white. He was big. And he wasn’t no shape at all. He was all messy and throbbing all the time, and he was all over little smooth wet wrinkles, all over the kind of white jelly he was. No eyes, no nothing. Only just all over kind of raw-looking. . . .

I just don’t like to think of Old Jellybags, kind friends. I just don’t . . . !

And the thing was that he had us—he had us there; and there wasn’t anything we could do. It was just as if you couldn’t even think. The thoughts were just drained right out of you, the way it maybe is if you are ever hypnotized, although I haven’t ever been hypnotized, so I don’t know, but I should think it was like that.

He was kind of finding out about us. It’s the only way to say it. It was his thoughts that were all around us, and he was probing and peering into us with those thoughts of his, and he was trying to find out what made us tick.

Our chums the Terrible Ones were all standing back a bit by this time. They were just standing all around like slaves or something. After all, they didn’t need to hold us anymore. We couldn’t move.

Well, what was the answer? How did we get away? ’Cos we did get away—you know that, else self wouldn’t be writing all this.

Lordy knows how long he had us there, feeling kind of sick, all three of us. Lordy knows.

But we did get away!

How?

Kind friends, you won’t believe it. But it worked. It worked for no more’n a split second or two, but it was all we needed. And the clue is what poor old Doc McGillivray said when he was telling the others about Old Jellybags: the Vivore couldn’t quite “fool all of the people all of the time.” No, sir. The process was kind of gradual. Once he had you, of course, he had you—the way he’d had Mac and Steve—but it took a little time till it was all complete—that was why those two had managed to go on sending messages right till the end, and it was also why—

However.

You see, I began to notice something. I began to notice that Old J.B. was so intent to get to know things in a hurry, sort of, that over and above the gradual-control stuff, he kind of took us in turn. He kind of concentrated a bit more on Katey for a moment, and then he concentrated a bit more on Mike for a moment, and then he concentrated a bit more on me for a moment. If we’d stayed much longer he’d’ve managed all three at once, but right at the beginning that was the way it was. ’Course, when he wasn’t concentrating on me, I still couldn’t move much, but I could, I just could think some of my own thoughts.

And it had all just dawned on me, and I was kind of relaxing for a minute in one of those spells, when suddenly I heard a whisper. Yessir! Right in my ear. I’d forgotten all about the whatsit inside our helmets that could make us hear one another. And it was Mike’s voice.

He says, “Maggie,” he says.

And it was a minute or two before I really got it that it was Mike speaking, but I did. ’Cos you see he was talking in Double-talk himself—that’s where the Double-talk comes in. It was really “Aggiemi” he said. And I tried to answer back in the same way. But I couldn’t, for all of a sudden Old Jellybags was concentrating right on me again, and there was no hope. But when he switched away from me onto Katey I managed it, ’cos there was Mike’s voice again, and he says:

“Maggie,” he says, very weak and faint, “can you hear me, Maggie?” (or rather: “Anci ooyi earhi eemi, Aggiemi?”)

And this time self makes it.

“Yes,” self says, “can hear you, Mike.”

And Mike says, still in Double-talk:

“You get the idea? It’s one of us and then another of us, and in the times between we can talk, the other two, just a little, not much, but enough.”

And self says yes, that self had jumped to it, and Mike says he had spoken to Katey in this way the last time it was me was the one being hypnotized, and that maybe we could work out something, and self says fine and dandy only what? And Mike says he has an idea and it maybe sounds silly but it might work, and just at that moment Old Jellybags swings around to concentrate on Mike and he has to shut up—but of course self can talk to Katey now for a little bit, and self and Katey have some dialogue along same lines before self is under the influence again in her turn.

Get it?

It took hours. All in Double-talk. I don’t really know why we did use Double-talk—except maybe it helped to make it all a bit more secret to us. We were all a bit dopey and it seemed a good idea at the time. ’Course, if Old J.B. had chosen to do a bit of concentrating on all of us together we’d’ve been caught out. He could have understood Double-talk just as easily as any other kind of talk—not that he could hear, of course, for he’d no ears, but it wasn’t words that mattered to him at all, but the thought behind the words.

Still, luckily he didn’t tackle us all three at once—and we took tremendous care right through only to talk when he wasn’t looking, so to say.

Well then: Mike’s idea for a way to escape seems just blamed silly when you set it down like this on paper—I’m almost ashamed to do it! But I told you we were very dopey when we were half under the influence, and it was all we could think of, and anyway it worked, kind friends.

Mike said (only it took a long time for him to say all this, partly to me and partly to Katey) Mike said: “You know back home,” Mike said, “when you’re with the gang, and you suddenly say to one of them ‘Look out behind,’ why you can be doggone sure that just for a split second he will look out behind. Well,” says Mike, “suppose we did that with Old J.B. in front there? ’Course he can’t look behind, we know that, but if we all three all thought at the same time, as hard as we could, that there was something dangerous behind him, maybe just for the one moment he would switch his thoughts away from us. And we can move so quickly on Mars that if we all made one great jump over to the left it would take us twenty feet at least, and then Old Jellybags wouldn’t be so strong in his power over us and we could jump again, and then again, and we might get away, right outside, and we would only have the Terrible Ones to cope with, and we could maybe outpace them if we took them by surprise.”

Well, Mike said all that, bit by bit, and in the old Double-talk, to each of us, and Katey and I talked about it too, when Mike was under the influence. And so we built it all up. And even at the time it seemed silly, but we had to do something, and it was a long shot.

Once or twice, as we worked it all out, there was the notion that maybe Old Jellybags was wise to us. He started switching from one to the other more quickly. But we kept it hidden by only doing a little bit at a time. And at last we were all ready.

“Next time,” says Mike, “—next time around and we’ll do it. He’s at Katey now. He’ll switch to me next. Tell Katey to be ready. Then after me he’ll switch to you. Now, you know there’s just a moment when you feel it all coming on as he does his full hypnotizing stuff? Well, just at that moment, when it’s coming to you and leaving me, do everything you can to shout what we’ve agreed to shout. Katey can do it at the same time, and so will I, just when the ’fluence is leaving me, you see. He won’t hear us, of course, but while we shout we’ll all three think at the same time, and the thought behind the shout will get over to him, and with luck it might work—he might just switch away from all three of us at the same time, and the minute you feel free of him, jump, my girl, as hard as you can!”

We did it.

We built it all up.

We had worked out what to say, you see. Not that it mattered what we did say—it was the thought behind it that mattered. If we could only believe it strongly enough ourselves . . .

I got the signal from Katey while Mike was under the influence. Then I felt Old Jellybags beginning to switch to me. And I screwed up all my concentration, every single ounce of it, and we all did shout at the same time, with a tremendous effort, and we almost deafened ourselves inside the helmets. And you’ll never guess what we shouted, and if it seems silly you’ll remember that we were all dopey when we worked it out, and anyway as I’ve said it wasn’t the words that mattered at all.

We shouted:

“Look out behind there! Paul Revere!”

It was all we could think of—it was all we could agree on. And we thought so hard, so hard. I know I thought so hard myself it was as if, just for the one quick second, I had a kind of vision behind Old Jellybags of that old hero we used to read about when we were very young, galloping to the rescue. There was a kind of shadow, very fleeting, in the forest beyond, of a great black horse and a man astride her, coming to save us. I thought so hard, you see.

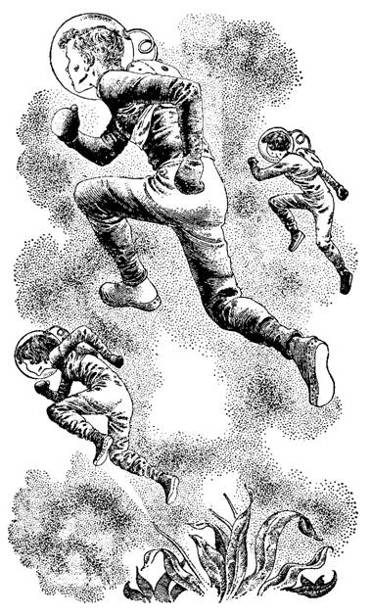

And it was the thought that did it. There must have been, just for a second, a sudden sense of some kind of danger from all three of us to Old Jellybags. He didn’t look around, of course—but he did switch his thought away from us, kind friends! I felt all of a sudden free—and I remembered to jump—and I was suddenly flying through the air with Mike on one side and Katey on the other!

And I was suddenly flying through the air.

And we landed right at the edge of the clear space in the Yellow Cloud. And at that moment Old Jellybags’ thoughts were back on us, and he was as angry as angry as angry. But his thoughts weren’t so strong this time, and we jumped again, right into the Yellow Cloud, and then again, and by now the influence had gone, and the next jump took us clear of the Forest altogether, and we were out in the open and running and jumping on the plain, and the air was all clear, and we could move and use our hands and our own thoughts again, and we fired and fired at the Terrible Ones who were chasing us after the first surprise, and we saw the others in the tractor far, far away before the Yellow Cloud came swirling out again all around us, and we ran on and on and on and on, and suddenly the Cloud all cleared when the tractor came into it with the flame throwers working full blast and there you have it, kind friends, you know the rest!

Cut! Cut!

Triumphant music!

THE END.

Next Week: Another Sherwood Production, featuring Bing Malone and Marlene Hogarth.

Phew!

Phew indeed!

It is how I invariably feel when I finish reading Maggie’s contribution here inserted—quite breathless, as she must have felt when she finished writing it.

So I resume then (Borrowdale writing again), with all threads in the narrative now tied, with the story’s progress complete up to the point when we routed the pursuing Terrible Ones and swung open the trailer covering to admit our rescued friends.

May I add only this as a last parenthesis—as a postscript to Maggie’s paper:

The method used to escape from the influence of Discophora may seem indeed, set down in cold black and white, to be somewhat trivial, as Maggie herself has said. But it must be emphasized that the principle lying behind it is more than sound. Not only did it work in practice in this particular instance, but it has, we believe, shown us the way in which we might combat the Vivores when someday we return to renew our contact with them. They are Brain, all Brain. In close proximity to them one cannot help but fall beneath their gradual telepathic control. The one way in which release can truly be found is indeed to contrive some method to divert the intolerably intense attention of that gigantic living intelligence. Maggie and her companions did so by concentrating their own intense thoughts on imaginary danger—so powerfully, for one split second, as to release themselves from the spell long enough to effect an escape. They thought of Paul Revere, the ancient hero of American history, because he constituted, to them, something normal and safe. They might equally well have concentrated on King Arthur, of British legend, or on Charlemagne of French. The words, the image, were of no importance—it was the sudden impression that achieved results, the sudden diverting of Discophora’s whole attention.

With this elementary but effective example before us, we have, since our return to Earth, been attempting to perfect a method operating on the same broad principle, which might help us to hold the attention of the Vivores for longer periods. It is, putting it briefly, an apparatus which should be able to oppose and annihilate the deadly thought-impulses from Discophora. We propose, in short, to counter the Living Brains of Mars with the noble Electronic Brain created by Man; and that will be a battle indeed!

It is a tale that is still to be told. This one must meanwhile be ended; and at its end, however we may come to control them in the future, the Vivores were our deadliest enemies.

We knew that most bitterly as we sped across the Cloud-swept plain toward our threatened Comet. In the excitement of our plunge forward in the tractor to rescue Katey and the others, we had, of course, ignored the danger signal transmitted to us from the photo-electric barrier apparatus set up around the rocket’s base. We had switched off the receivers within our helmets so as to be free from the distraction of the high-pitched frequency hum. Now, with the rescue completed, we retuned—and heard the signal again, insistently. The Comet was indeed in danger—something had penetrated the barrier.

And we knew in our hearts, as we speeded forward through the mist, guided by the beamed signal itself—we knew what the danger was. We remembered the arrowhead of Yellow Cloud we had seen from the plain, outthrusting from the “tail” of the Ridge. We knew it now for what it was: a messenger, sent out by our own Discophora to heaven knew how many of his fellow Vivores.

The great Creeping Canals had assembled—across the vast plain they had marched to surround our spaceship. They had reached the very base itself. To win to safety we would have to pass through the deadly controlling zone of them—somehow.

We went forward, always forward, our one hope to reach the Comet before, perhaps, she was entirely surrounded. We were all together again. And yet—and yet!—

We were not all together. Two members of our party were missing. The knowledge did not come to us for some time—until we were well on our way from the original Ridge. In the seething confusion of the moment when Katey and Mike and Maggie had clambered into the trailer, two figures had, unnoticed, slipped out into the swirling Cloud. We in the tractor thought they were in the trailer as we went forward toward the Comet—our friends in the trailer took them to be in the tractor.

They were in neither. We had gone too far to turn back when, through the communication apparatus, we heard a cry from Katey. She had come across a folded note, the script on it spidery and uncertain, its corner held by the lid of one of the lockers.

It was addressed to Dr. Kalkenbrenner. He asked her to read it and we all listened to her voice in silence—and I, in my mind’s eye, saw the stooping, writing figure of Dr. McGillivray during our long groping journey through the Cloud. . . .

Katey read:

My dear Kalkenbrenner, the danger signal from your ship can mean one thing only: that Discophora surround it, probably in considerable numbers. They will do all they can to prevent your reaching it. But you must reach it, you must You must go back to Earth and take my dear young friends out of the terrible danger to which I feel I have been instrumental in exposing them.

I am blind and helpless. But there is a way in which I may be able to help you. I have discussed it silently with Malu. I need him as a guide in my sightless state, but also he wishes to assist me, and comes out with me in the true spirit which actuated Captain Oates.

I write this as we journey to rescue Miss Hogarth and the others. Malu and I will contrive to slip out of the trailer—with good fortune you may not notice our absence for some little time. Do not try to come after us. It is my last wish that you should go forward and win to safety.

My plan is wild. It may not succeed. But I shall try my best. You will know, when the time comes, what it is I have done.

God bless you all. Your true friend in the eternal cause of science—

Andrew McGillivray

The silence held as Katey finished reading. Her voice was very quiet, imbued with the strange solemnity of the words of McGillivray’s enigmatic note.

“Captain Oates,” said Jacqueline softly. “Captain Oates, Paul . . . ?”

And Paul answered gravely:

“Don’t you remember, Jacky? In Captain Scott’s last expedition. The one who went out from the tent into the blizzard to try to save the others—went out to his death. . . .”

Around us indeed, in the little moving “tent” in which we clustered, the yellow blizzard tossed and swirled.

“But how—how?” asked Michael. “How can he save us?”

To that compelling question there was no reply. We knew nothing—not even where to look for McGillivray if there were any question of going back for him. We could do no more than obey the final wishes of our lost companion. We went forward, always forward.

Around us, as the distance from the Ridge grew greater, the Yellow Cloud was thinning and dispersing. There came a time at last when it was possible to steer visually. As the last wreathings of the mist dissolved, we saw far, far ahead across the plain, the slender gleaming spire of the Comet.

We drew nearer. And it was as if, indeed, the great rocket stood at the center of a gigantic spider’s web. Over the plain had converged a veritable network of the deadly green Creeping Canals, each housing, as we knew, in its steamy depths, a single member of the dying race of the Vivores.

The air was clear now—there were no further traces of Cloud. We still went forward, nearer and nearer. It was the one course possible. The throb of our engine was the only sound in all the vast and menacing scene. But, mingling with it in our heads, at one moment—faintly, infinitely faintly as he made the immense telepathic effort over the distance separating us, from wherever he might be—there came the “voice” of Malu: “Farewell, my friends. Again remember Malu the Tall, Prince of the Beautiful People. Farewell—this time a last farewell. . . .”